The confounding – maybe even terrifying – rise of cause marketing.

This is kind of a weird time for advertising. I realize I’m not exactly challenging the seaworthiness of the Good Ship Conventional Wisdom with that anti-linkbait of a thesis. But if I start with understatement, that gives me permission to devolve into overblown, unhinged bombast later. At least, that’s my strategy. Which I’m only telling you now because I respect you too much to treat you the way all those other think-piece writers do.

Anyway, weird times, though, for real.

I mean, even by the standards of the protracted death-of-print and rise-of-social upheavals of the past decade or so, this latest shift feels different. Weirder. Weirdest ever, maybe. Maybe even weirdest theoretically possible. OK, too far. But let’s at least agree that the only thing weirder than the weirdness itself (which we’ve already established is weird) is that hardly anyone seems to be calling out the actual level of this current weirdness for being so particularly weird. It’s almost like waking up in an airplane cabin filled with smoke and finding your fellow passengers calmly working Sudoku puzzles.

A hell of a lot of ink has already been spilled on this peculiar moment, I know, but what no one seems to have captured in print so far is the subjective texture of how thoroughly strange one particular subset of this current weird soup is. The subset we’ve collectively decided to call “cause marketing” (terrible, terrible name, that, but that’s a topic for another article). Sure, we generally recognize that something kinda new is happening, but if any of us ad industry types were to stop and really look the thing in the face, I suspect we’d be left either packing provisions and heading for the hills or waiting on the roof for the crystal spaceships.

So it’s worth saying it one more time, if only to compensate for the collective disregard up till now: This. Is. Weird.

Somehow, after generations of unfettered corporate greed, after an age where we elevated mass-manipulation to an art form, suddenly now everyone cares about corporate social responsibility? About helping the helpless and solving the insoluble? One day the sun goes down and the next it’s glittering over a world where Capitalism contends with Cosmic Justice? And we’re just supposed to shrug and accept it?

In the blink of an eye, corporate Good has become big. Two-billion-dollars-a-year-and-growing big.

I’ll tell you this much, no one writing 20th century dystopian Sci Fi saw that one coming.

How does the ad industry respond to that? At the risk of unfair generalization, we as a group are not exactly emotionally equipped for dealing with this kind of earnest sincerity, are we? So we can adopt our default change-posture of black-clad cynicism, we can be suspicious, we can call it a flash in the pan, this generation’s brief flirtation with Free Love: Corporation Edition. We can question the motives of everyone involved. I certainly have. Or we can do what most of us are already doing: ignore it entirely. The one thing we can’t do: pretend that this is anything but a very good thing.

Putting aside how we feel about it, and I’m still deeply conflicted on that point myself, who has more power to change the world for the better than corporations? The non-profit sector? Too under-resourced. The volunteer corps? Too disorganized. The church? Too preoccupied with stadium-seating multi-media immersion-worship arena design. The government? Too busy with finger kissing and baby pointing. (Notable exceptions to all four notably noted).

Face it. The only power structure in which 100% of the populace engages and participates with 100% of their attention is the corporate state.

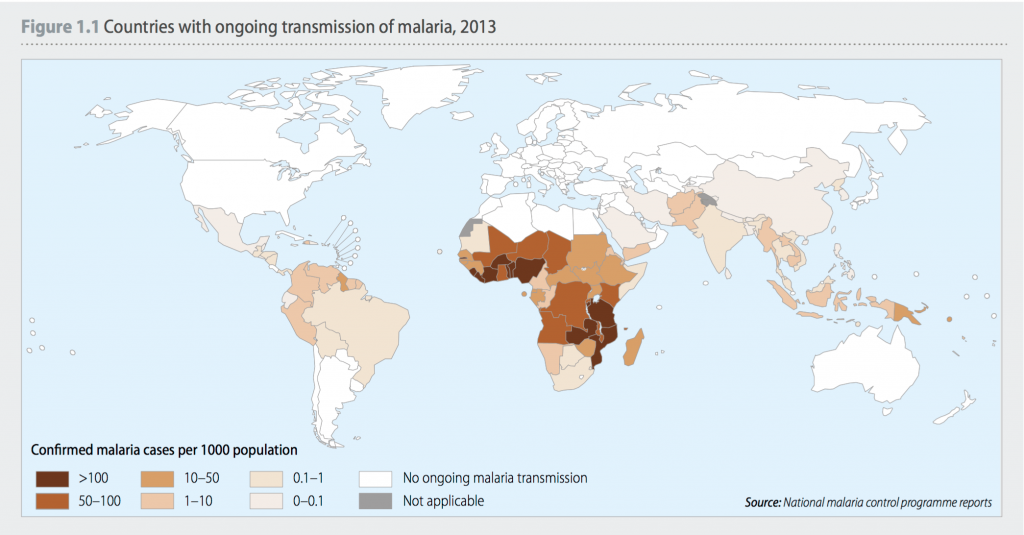

If anyone can end illiteracy, inequality, the spread of disease, the relentless choreography of gross, systemic injustice, it can.

I can’t even believe I just wrote that sentence. But there it is.

A cynic would point out that the corporate state can (and has) also fueled each one of those things when it was convenient to do so. And that cynic would be right.

But this bravish new future hinges on a strange kind of tension. It asks the consumer to shed one cloak of cynicism and don another. To silence the inner Idealist Cynic and pass the microphone to the inner-Pragmatist Cynic.

Whether consumers can successfully shoulder the cognitive dissonance required to do so remains to be seen. And whether the ad industry at large can figure out how to cautiously participate in this transition without triggering a massive, cynical counter-reaction is an even bigger open question. But the corporate state is forging ahead with us or without us.

And, by all accounts, it is doing some real good. Or, at least, it’s beginning to. Water is being drawn for the thirsty. The naked are being clothed. The curious taught.

Why, though, is the corporate state doing this in the first place? For the only reason it does anything. People are demanding it. They are voting with their debit cards. Consumers have successfully convinced (or conned, depending on your point of view) the most powerful entities on the planet that what they most want to buy is a brand that helps.

How did this happen? How did the great manipulated learn to manipulate the great manipulators? And why, suddenly, are people concerned with mass, social good in the first place? The same consumers who for generations have been preoccupied with the latest luster of the utterly trivial?

We’ll leave the final word on those questions for Marketing History, should that ever turn out to be a thing that undergrads willingly sign up for, shudder.

But I have a theory. OK, theory is much too generous a word. Let’s call it a proto-hunch. A proto-hunch with an excellent chance of being dead wrong. But maybe it’ll prove to be just true enough to be useful.

It goes like this:

For decades, we advertisers have operated under the auspices of The One Great and Powerful Lie. TOGAPL. It has been the chief driving principle of every ad we’ve ever produced, the last unmentionable secret of the craft. TOGAPL is the ad industry’s golden goose, the blessed lie that keeps on giving. And it is this: that when you, the consumer, buy a product, you aren’t really buying a product. You’re buying an image.

Want to look successful? Buy a german car. Want to appear sexually competent? Buy a lite beer. Want to look sophisticated and independent? Buy a Mac.

The thing about this lie is, it works. Or, it has worked, anyway, and it has worked like a charm. (Unrelated, but when did charms become the barometer by which the efficacy of all other items is judged? Do charms really themselves work like charms? If so, why aren’t we hearing more about it?)

An inexpressibly large chunk of the entire western economy has been directly fueled by this one technique: the selling of image. But now its power, by all indications, is waning. The charm is uncharming.

You don’t have to look far to see the evidence. You still see image marketing, mind you, but with every passing year it seems to be more confined to ads aimed at older demographics. Hey you, middle-income, 50-something man: wanna seem tough? Buy a pickup. Hey mid-life-crisis-denying cubicle cog, wanna remind yourself and everyone around you of your raw virility? Buy an American sports car. For those who grew up in the golden age of TOGAPL, it works as well as it always did, no one bats an eye.

But below that middle-aged ceiling, it’s another story entirely. With millennials, the reliable old con shows signs of serious strain, for reasons I’m about to speculate wildly on. In this demographic, we’ve even recently begun to see TOGAPL’s near-exact inverse: the ad directly mocking image ads. Old Spice comes to mind, as do recent Newcastle, Skittles, Burger King and Keystone Light campaigns. The decidedly ironic reincarnation of the Brawny man. “Far less attractive Rob Lowe.” Etc etc and etc.

There’s still image marketing at work in all these examples, mind you, it’s just that the image being sold is now one of seeming not to care about image. Which is interesting (and I suspect will get more interesting as this territory becomes over trodden and tiresome). It’s also a clue as to what’s really happening in the psyches of modern young adults.

What’s really happening, and this is the even more speculative part, is that this new generation has been so oversteeped in such a preposterous volume of messaging that they’ve unwittingly assimilated the entire advertising project and now see straight through it. Like they were L Ron to advertising’s Xenu. Or Johnny 5 to advertising’s …. um, advertising.

Forget it. What I’m saying is, you take the entire mass of image marketing noise the rest of us encounter in a lifetime and stack it up? It’s trivial compared to how these kids have grown up; the millennials devoured more messaging while they were still in diapers than I have in my whole life. Ads to them are the city street-stink you never notice until you’re sitting in the middle of nowhere and find it missing.

Dialing the speculation potentiometer up another notch, maybe what’s going in is that millennials have developed an exposure immunity (level: sewer rat) to image marketing. Maybe they bought the lie hook line and sinker for the first decade or so of their lives, maybe we marketers fooled them the first few thousand times. But now, after buying their 1,287th Coca Cola and realizing that, once again, it has not in fact provided lasting happiness to themselves much less the whole world, they’re finally onto us.

Maybe now their immunity to image salesmanship is so beyond what we can guess that they recoil at every one of our hackneyed attempts to manipulate their desires, and at the un-self-awareness we betray by even attempting to sell image in the first place.

There could be a pornography analog (I know, Beavis) here, too, probably. Maybe more than just an analog. Who knows, maybe it’s part of the same feedback loop above. What I mean is that these kids have grown up as the first group in history with unfettered access to whatever flavor of sexual intrigue they could ever dream up. So what happens when these kids grow up, sexually speaking? Now the data here is a little contradictory, and we may be guilty of cherry picking the parts that support our slick narrative, but if you look into it, sure enough, there issome evidence that while millennials aren’t getting married as much, they may in fact be more monogamous than the generation before them, less sexually risky. How is this relevant? Maybe when you grow up in the vomitorium, gluttony is no longer cool.

We’ve raised a generation surrounded by funhouse mirrors. Should we be surprised that their relationship to image is complicated and contradictory? Is it really that much of a shock to see the selfie-generation leading the charge against image manipulation?

The point here is just that this group of young adults, the most coveted demographic in all of marketing, wants none of what we’re good at selling. They don’t want ego validation by purchase. What they want, and this is as well-validated in the research as it is shocking, is meaning. This is preposterous, so much so that if it hadn’t been for the publicity these studies have gotten, you’d assume we were making this up, or joking. Millennials want meaning in their careers (more than they want better compensation). They want meaning in their free time. They even want meaning in their purchases. And they’re rewarding brands that give them so much as a taste of it.

Think about it. This is not supposed to happen until one’s 40s. How jaded and world weary, how let down with the entire American consumption project at the delicate age of 22 do you have to be to put “meaning” at the top of your priority list, ahead of “fast car” and “fun friends”? This is, we think, a much bigger story than anyone has told yet. It’s potentially, if you’re the panicky type, the story of the collapse of the entire western way of life. (And if brands don’t quickly respond to this by radically rethinking how they engage in the world, that hypothetical panic may prove to be merited.)

And all of this is on us. Advertisers. We’ve pushed them here. We have pushed them so far so fast that they had to grow up. It was their only viable option. A mass awakening. A media maturation so startling that it’s left us media manipulators entirely behind. We have, through overplaying our image hand, caused the audience to develop psychologically at a rate we ourselves are incapable of matching. (I’m speaking for myself here, at least – part of my brain, despite knowing better, is always going to think of purchasing an Audi as a courageous act of corporate rebellion).

So this is what we’re dealing with. This is why this cause marketing explosion thing may not be just a temporary fad. The current flavors and tactics of cause marketing will undoubtedly prove temporary and fad-like, but the category itself is here to stay.

The audience has grown up. They want the one thing in their purchasing that we advertisers don’t know how to offer. They want a story that’s bigger than themselves. They want meaning.

If we’re going to catch up with the audience, we’re going to have to be smarter. We’re going to have to move past our clumsy early attempts to deal with this cause thing. We have to stop painting a veneer of meaning over the same basic image-selling project.

Now let me admit, I could well be wrong. This is not settled science. You could even argue that millennials don’t truly want anything new. That all they’re asking is for brands to sell them a new image: an image of social usefulness. According to this camp, millennials are less concerned with actually doing good than with feeling like they’re doing good. Or, more to the point, with proving their moral mettle to their peers with TOM’s logos and product (RED) gear. It’s a compelling argument. Both marketing history and human psychology would probably lean this way.

But my partners and I are putting our own money, literally, in the other camp. Given that this camp is the naïve and earnest one, it might be a mistake. We’re willing to risk it. Because we’re betting that that’s not how this will play out.

We believe that we’re witnessing a fundamental change in the market. That what we see stirring first in Millennials is a bona fide mass awakening, an audience rubbing the sleep out of its collective eyes and mumbling, “but I’m not sure I want to obey my thirst.” Our money says that this early morning mumble turns into a roar well before lunch time. That this is not just a quick hiccup in advertising’s oldest project. That this may in fact be the beginning of the end of that project.

Sure, maybe these two camps don’t line up quite as neatly as we’re saying. And maybe the battle line demarcated here is one that runs down, to paraphrase Solzhenitsyn, the center of every sternum. Fair enough. If we have to hew to a side of our own hearts, we want to pick the sincere side.

And the sincere side of our own hearts tells us to believe in consumers. To hold to the possibility that this generation no longer cares mainly about satisfying their own desires. Or said slightly less idealistically, that maybe they’ve elevated a new desire to compete on equal footing with their other desires: the desire to make the world a little better for everyone.

Where it goes from here is anyone’s guess, but we have a strong suspicion that consumers aren’t going to continue supporting just any brand that pays lip service to doing good. That they will get savvier and more involved, and they will reward the companies doing the best, most sustained good. And they’ll do it even if no one knows they’re helping, even if they don’t get a logo to wear proving they’re involved.

If you’re going to bet against this new desire taking root and becoming more and more important in the American marketing landscape, that’s your prerogative. But there’s something you should know first, and it’s this: the old slope was built on self-indulgence, and it was trending downwards from the day the first ad ran. This new curve, it’s sketchy and erratic right now, granted, but it could well be different. It might very well be that unlike the old desires of American consumerism, the ones that wither under the frustrating inefficacy of their feeding, the ones that slowly deaden with every iteration of their own trivial fulfillment, this new desire gets stronger the more it’s fed. Helping is, in a word, habit forming. Crap, that’s two words. Helping is, in two words, habit forming.

Good, we believe, is here to stay. Not because good looks good. But because good is good. And if this new union between consumerism and corporate, self-interested selflessness proves to be sustainable, the biggest irony will be that it took the same generation that invented the selfie to lead the way.

Pad Pals.

Pad Pals.

Our idea:

Our idea:  If this were an actual paying client exploration, we’d do a full-scale naming study for this, and land on something catchy, domain-available, and trademark free. But since this is a free idea, we’ll call it the first thing I think of. Which is SharkScan.

If this were an actual paying client exploration, we’d do a full-scale naming study for this, and land on something catchy, domain-available, and trademark free. But since this is a free idea, we’ll call it the first thing I think of. Which is SharkScan.

To be clear, as far as we know, Orkin has never heard this idea. Despite connections (and interest) at their agency of record, we’ve been unable to land a real meeting with them. So when you hear this idea and think “Those assholes! How dare they pass this up,” just know they haven’t actually passed it up. But this is now public domain, it’s theirs to take and run with if they want it. So if this post were somehow to end up on the desk of, say, Glen Rollins, Orkin’s CEO, (or the desk of Bill Derwin, president of Orkin’s biggest competitor, Terminix) we would not complain.

To be clear, as far as we know, Orkin has never heard this idea. Despite connections (and interest) at their agency of record, we’ve been unable to land a real meeting with them. So when you hear this idea and think “Those assholes! How dare they pass this up,” just know they haven’t actually passed it up. But this is now public domain, it’s theirs to take and run with if they want it. So if this post were somehow to end up on the desk of, say, Glen Rollins, Orkin’s CEO, (or the desk of Bill Derwin, president of Orkin’s biggest competitor, Terminix) we would not complain.